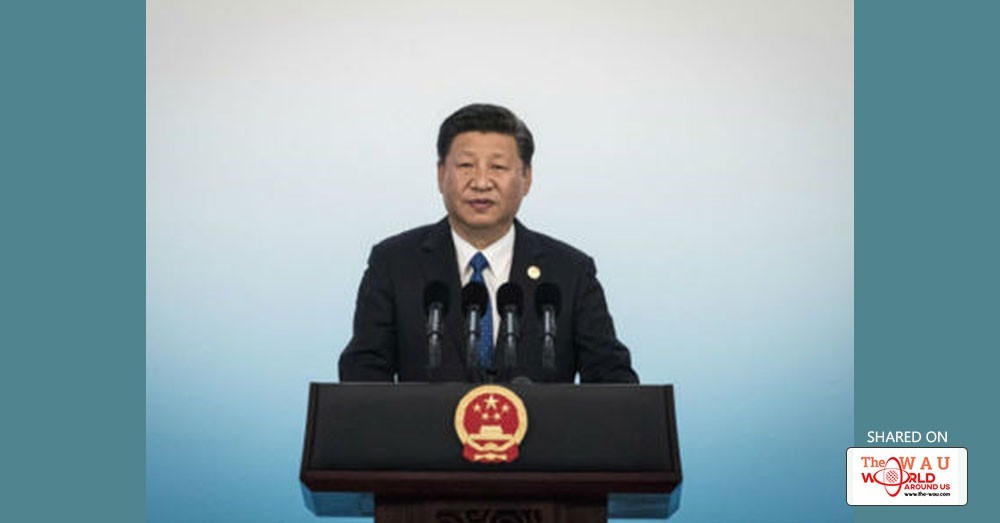

Events like Doklam and North Korea's nuclear test present unexpected challenges to Chinese President Xi Jinping's stated resolve to realise the "China dream" and he may face a difficult choice in deciding whether to persist with strong projection of power or adopt a more sedate course.

The incident at Doklam could be termed small in Xi's scheme of things, which includes rivalling the US economically and militarily, keeping China's vast neighbourhood quiescent, neutralising hostile power centres within and, above all, maintaining the primacy of the party in running China's affairs.

But the stakes at Doklam became higher than warranted due to the intensity with which China launched a media and diplomatic blitz against India's "illegal" occupation and New Delhi's success in sitting out the threats in hostile weather in the remote plateau on Bhutan's north-west.

The tactical retreat, though by no means permanent, was noted by world opinion as it stood in contrast to confident predictions of an Indian withdrawal.

The fresh trouble caused by North Korea's nuclear truancy at a time when Xi was hosting Brics complicated his sustained efforts to revalidate the authority of the Communist Party of China (CPC). When he took charge as general secretary, Xi was keen to bolster the legitimacy of the Communist Party which he saw as essential to managing new challenges such as social media, NGOs and rising public expectations.

His ruthless campaign against corrupt "tigers" snared five top national leaders and is intended as much to eliminate rivals as to instil faith in a system where the usual checks of a free press, elections and independent judiciary are unavailable.

In a recent paper, Harvard's respected China hand Prof Antony Saich noted if harder reforms are not feasible, Xi's policies could alternate between soft and hard authoritarianism. Dislodging the system's current beneficiaries will be difficult and in time an "illiberal democracy" could emerge with a dominant executive but a fragmented civil society. This is hardly an outcome Xi will envision. The more assertive projection of power and increasing recourse to nationalist sentiment has mirrored Xi's image as "chairman of everything" as he gained more power and came to be "core leader".

Global projects like One Belt, One Road indicated that China was looking for a more international role even as the programme was intended to maintain the momentum of a slowing economy.

If recent events, that include stronger differences with Japan, a possible re-engagement in Asia by the US post-North Korea's nuclear tests and efforts by Indonesia, Singapore and Vietnam to ensure free maritime passage in the South China Sea, deliver a reality check, then a recalibration may be in order. But the consequences of any policy shift can be internal too.

The party must explain whether China remains on course to realising its stated destiny to becoming a leading nation and also cater to higher expectations of transparency. The entrenched elites are unlikely to accept institutional reform that hurts them. Xi could look for a less bellicose phase with neighbours and turn his attention to fixing internal problems like state-owned firms and shifts in economic policy. But he can also be wary of signalling a weakened hand and iterate his commitment to Chinese hegemony.

Share This Post