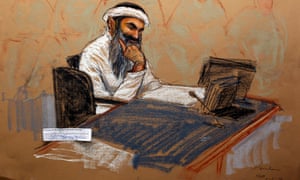

Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the accused “architect” of the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, will spend the 16th anniversary of the atrocity sitting in Guantánamo Bay, preparing for his 25th pre-trial hearing.

That hearing will take place next month. Military prosecutors’ latest estimate is that jury selection in Mohammed’s terrorism trial will begin in January 2019. Most interested experts think that is wildly optimistic and are asking if a man arrested in Pakistan in 2003 will ever stand trial at all.

“It will take another two, three or four years to get the case to trial and it will take a year or so to try,” the 53-year-old’s lawyer, David Nevin, told the Guardian.

Nevin estimated there would likely follow an initial appeal that could take five years, then that appeal going up to the circuit court – another three or four years – and, maybe four years after that, a conclusion in the US supreme court up to 18 years’ from now – 34 years after the attacks.

“There’s every possibility that my client will die in prison before this process is completed,” said Nevin.

“I don’t have the life expectancy statistics of someone in a US prison, also taking into account it would be someone who’s been tortured, but I’m sure it’s lower than normal. So you have to ask, why exactly are we doing this, or doing it in this way? We are spending millions and millions of [public] dollars every week for something that could be pointless.”

Terry McDermott, a co-author of the book The Hunt for KSM, attended Mohammed’s 24th pre-trial hearing last month.

“KSM already looks like he’s 83, he’s like a little old man,” he said. “He still has black eyebrows and he dyes his beard with henna but his hair is completely white. It’s that vision of the banality of evil.”

A small group of relatives of those who died on 9/11 also attended the August hearing. The case, handled by a military tribunal, seemed as far from conclusion as ever. The defense is campaigning to have the judge and prosecutors disqualified, accusing them of secretly allowing the dismantling of one of America’s overseas covert “black sites” where Mohammed is believed to have been persistently tortured, thus destroying vital evidence. The prosecution is seeking the death penalty, which the defense bitterly opposes.

Ellen Judd, 66, a Canadian anthropology professor at the University of Manitoba, attended the hearing and watched Mohammed and his four co-defendants through a triple-layered glass partition.

“It took a lot to steel myself for that,” she told the Guardian.

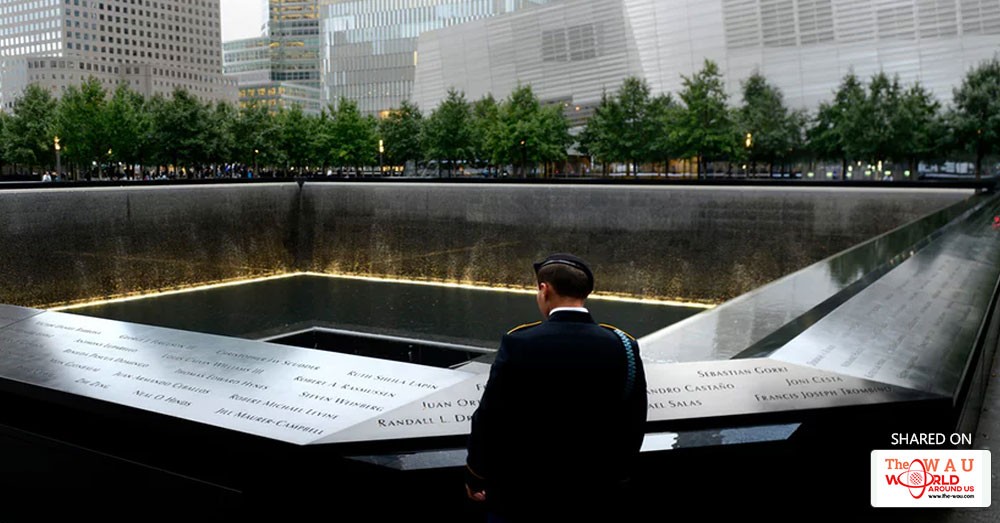

When hijackers flew passenger jets into the towers of the World Trade Center in New York, killing more than 2,700 people, Judd lost her partner of 15 years, Christine Egan.

Egan’s brother worked in one of the towers. She had chosen to visit him that morning. Egan, 55, and her brother, originally from Hull in England, were both killed. Egan had worked in healthcare and research among Inuit communities in northern Canada.

“The sense of loss is never over,” said Judd, adding that the presence of relatives at the court hearings was important. “It’s part of the grieving process, part of remembrance but it’s also to witness,” she said.

She wants the court to do its job and bring the case to conclusion, she said, but thinks the whole process of justice via a military commission falls short.

“I would have preferred something much more expansive,” she said, “a framework to arrive at how this all happened and routes to do something to resolve conflict in the world not perpetuate it. Something more like an international criminal tribunal.”

Karen Greenberg, director of the Center on National Security at Fordham University school of law in New York, argues that Mohammed’s case should be brought back into the US civilian court system, where it was on the verge of being tried in 2009, until the government decided it was altogether too risky to do so.

Despite a later change in the law to prevent Guantánamo detainees from being brought to the US proper, she believes KSM and the other defendants should be tried in a New York or Washington federal court by video link.

“We have to try them,” she said. “This delay is shameful. It’s destructive and it casts a shadow over the American justice system. As a nation, you cannot bring closure to the events of 9/11 while you have people in custody awaiting trial on this. The American people are being deprived of justice.”

Nevin would not comment on what could push the legal process forward. The defense team’s adamant opposition to the death penalty in the case, however, could could offer leverage.

McDermott said he could imagine a deal being struck where the defense gives up its campaign to remove the judge and prosecutors, in return for the government dropping its insistence on trying a capital case.

In a 26-page transcript released by the Pentagon in 2007, Mohammed is cited as confessing to having decapitated the journalist Daniel Pearl and claiming responsibility for dozens of terrorist attacks and plots.

“I was responsible for the 9/11 operation, from A to Z,” he is quoted as saying.

However, he has not yet formally entered a plea and it is unclear how much evidence there will be that is not tainted by allegations of torture. That and the problem of huge amounts of classified material are two issues slowing the case and hampering its chances of ever being brought back to a civilian court, Nevin said.

Michael Bachrach, an attorney who represented Ahmed Ghailani, the Tanzanian al-Qaida terrorist convicted in New York in 2010 for his part in the 1998 bombings of US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania, disagreed.

“Mohammed should have been brought to trial years ago,” he said. “I believe he could get a fair trial in federal court – the Ghailani case proved that. We had classified and unclassified material involved, torture involved, and the jury saw what was necessary for them to see.

“Can Mohammed get a fair trail by military commission? I’m not as confident about that.”

Ghailani was acquitted on 284 of 285 charges but convicted and sentenced to life without parole.

“I think it’s a true example of justice being done,” said Bachrach.

What did he think about the seeming endlessness of the KSM case?

“Truly awful.”

Share This Post