Dr. Rick Potts studied the pattern of climatic turnover in the fauna and the occurrence of archeological sites at Olorgesailie and another site in southern Kenya, and found that several large mammal species that had previously dominated the fauna of this region went extinct between about 700,000 and 300,000 years ago, during a period of repeated environmental instability. These species were replaced by modern relatives, which tended to be smaller in body size and not as specialized in diet or habitat.

For example, the zebra Equus oldowayensis had large and tall teeth specialized for eating grass. Its last known appearance in the fossil record of southern Kenya is between 780,000 and 600,000 years ago; it was replaced by Equus grevyi, which can graze (feed on grass) as well as browse (feed on leaves and other high-growing vegetation). The fossil baboon Theropithecus oswaldi, which weighed over 58 kg (over 127.6 pounds), lived on the ground exclusively; it had very large teeth and consumed grass. It also went extinct between 780,000 and 600,000 years ago. Its extant relative, Papio anubis, is omnivorous and moves easily on the ground and in trees. Two other large-bodied animals that specialized in eating grass, the elephant Elephas recki and the ancient pig Metridiochoerus, were also replaced by related species that were smaller and had more versatile diets (Loxodonta africana and Phacochoerus aethiopicus). The aquatic specialist Hippopotamus gorgops was replaced by the living hippopotamus, which is capable of traversing long distances between water bodies.

The replacement of the specialized species by closely related animals that possessed more flexible adaptations during a time of wide fluctuation in climate was a key piece of initial evidence that led to the variability selection hypothesis. Although Acheulean toolmaking hominins were able to cope with changing habitats throughout much of the Olorgesailie record, the Acheulean way of life disappeared from the region sometime between 500,000 and 300,000 years ago, perhaps also a casualty of strong environmental uncertainty and changing circumstances.

Encephalization and Adaptability

Brain enlargement during human evolution has been dramatic. During the first four million years of human evolution, brain size increased very slowly. Encephalization, or the evolutionary enlargement of the brain relative to body size, was especially pronounced over the past 800,000 years, coinciding with the period of strongest climate fluctuation worldwide. Larger brains allowed hominins to process and store information, to plan ahead, and to solve abstract problems. A large brain able to produce versatile solutions to new and diverse survival challenges was, according to the variability selection hypothesis, favored with an increase in the range of environments hominins confronted over time and space.

New Tools for Many Different Purposes

After 400,000 years ago, hominins found new ways of coping with the environment by creating a variety of different tools. In some parts of Africa, a shift occurred in which a technology dominated by large cutting tools was replaced by smaller, more diverse toolkits. Technological innovations began to appear in the Middle Stone Age in Africa, with some early examples dating prior to 280,000 years ago. Some of the new tools provided ways for hominins to access food in new ways. Points were hafted, or attached to handles such as spear or arrow shafts, and were later used as part of projectile weapons, which allowed hominins to hunt fast and dangerous prey without approaching as closely. Barbed points were used to spear fish. Barbed points made from bone were found at the site of Katanda, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, along with the remains of huge catfish. Grindstones were used to process plant foods. Other tools were used to make clothing which would have been important for hominins in cold environments.

Regional Exchange and Social Networks

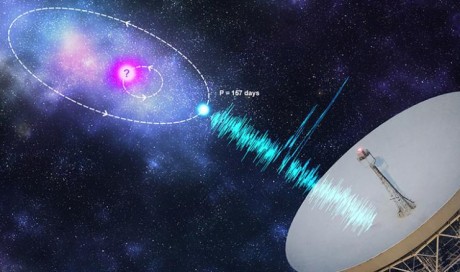

Over the past 300,000 years or so, the direct ancestors of living humans developed the capacity to create new and diverse tools. Archeological discoveries show that wider social networks began to arise, enabling the transfer of stone material over long distances. Symbolic artifacts connoting complex language and the ability to plan are also evident in the archeological record of the Middle Stone Age of Africa. These findings indicate an improved capacity to adjust to new environments. Most of the past 350,000 years in East Africa was a time of strong climate oscillation. The timeline at the bottom of the image is 280,000 to 40,000 years ago (right to left). This figure is based on an analysis by archeologists Sally McBrearty and Alison Brooks.

Trading between groups to obtain materials and to cement alliances is a hallmark of modern human behavior. Larger brains and symbolic ability facilitated more complex social interactions. By 130,000 years ago, hominins were exchanging materials over distances of over 300 km. The social bonds that were forged by exchanging materials between groups may have been critical for survival during times of environmental change when one group relied on the resources or territories of a distant group. Modern foragers use social ties to mitigate the effects of famines and droughts. The exchange of gifts maintains relationships between groups, which may be called upon when one group needs to live at another’s camp or waterhole, a capacity that proved especially beneficial during times of environmental change and resource uncertainty.

Communication and Symbols

Engraved ocher plaque from Blombos Cave, Republic of South Africa; about 77,000–75,000 years old

Evidence of the human capacity for communication using symbols is apparent in the archeological record back to at least 250,000 years old, and probably older. The use of color, incised symbols, decorative objects, and language are part of this capacity for communication. Symbolic communication may be linked with information storage. Language is an essential part of modern human communication. Language makes it possible to convey complex ideas to others. Communication of ideas and circumstances via language would have made survival in a changing world much easier. However, there is no fossil evidence for words and grammar that are the direct hallmarks of human language.

Preserved pieces of pigment are one of the earliest forms of symbolic communication. Ocher and manganese can be used to color objects and skin. Other symbolic objects such as jewelry, personal adornments, and art convey information about the owner’s social status, group membership, age or sex. Paintings and drawings were also used to represent the natural world. Use of symbols is ultimately connected to the human ability to plan, record information, and imagine.

Neanderthals Endured Climatic Oscillations, Too!

Neanderthal populations (Homo neanderthalensis) in Europe endured many environmental changes, including large shifts in climate between glacial and interglacial conditions, while living in a habitat that was colder overall than settings where most other hominin species lived. Some of the environmental shifts they endured involved rapid swings between cold and warm climate.

The Neanderthals were able to adjust their behavior to fit the circumstances. During cold, glacial periods, they focused on hunting reindeer, which are cold-adapted animals. During warmer, interglacial periods, they hunted red deer. During extreme cold periods, they shifted their range southwards toward warmer environments.

Neanderthals and modern humans had different ways of dealing with environmental fluctuation and the survival challenges it posed. Modern humans, Homo sapiens, had specialized tools to extract a variety of dietary resources. They also had broad social networks as shown by the exchange of goods over a long distance. They used symbols as a means of communicating and storing information. Neanderthals did not make tools that were as specialized as those of modern humans who moved from Africa into Europe sometime around 46,000 years ago. The Neanderthals usually did not exchange materials over so wide a distance as Homo sapiens. They occasionally produced symbolic artifacts. Despite many climatic fluctuations, modern humans were able to expand their range over Europe and Asia, and into new areas such as Australia and the Americas. Neanderthals went extinct. This evidence suggests that adaptability to varying environments was one of the key differences between these two evolutionary cousins.

During the time when Neanderthals evolved in Europe, global climate fluctuated dramatically between warm and cold. The highlighted area on the right side of the graph represents the last 200,000 years.

...[ Continue to next page ]

Share This Post