Like most people in the US, I hadn't been aware of the scale of the refugee disaster until the pictures of three-year-old Alan Kurdi washed up on a beach started being shown on US news in 2015.

But it wasn't until I actually got here and saw for myself the piles of life jackets and the boats stacked on the beach that the magnitude of it really hit me.

I had taken a leave of absence from my job and planned to be in Greece for 45 days. My assumption was that I would find people who were housed, fed, and had basic services available.

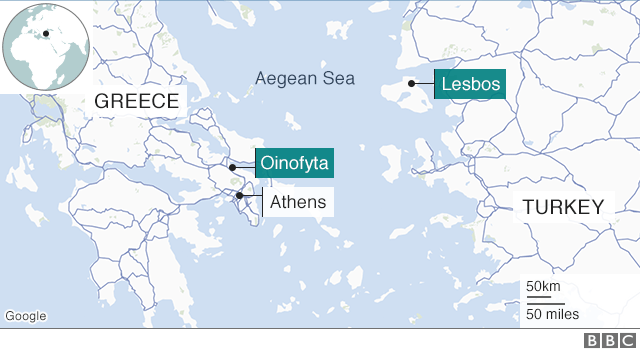

That first morning on the island of Lesbos, I went out on my balcony and I could see nine boats coming across from Turkey already. You hear people say that the boats are overloaded, but to see 50 people get off of a boat that would be full with 10 is overwhelming. I can't tell you how many times people would get off the boat and literally kiss the ground. That grabs you.

It was hard to wrap my head around what I was seeing. I was horrified at the stories that I heard. I was also happy to be able to help, happy to see that these children, once you got them into some dry clothes, were still looking for the first toy they could find.

There's probably not an emotion that I didn't experience, standing there day after day on the shore, watching the boats come in. And that's how my journey in Greece started.

When I got to the refugee camp in Oinofyta, on the mainland north of Athens, there was nothing there - just tents and army catering. I had no refugee experience, but I'm a do-er. After Hurricane Katrina, I helped start a non-profit called Do Your Part. We had worked in disaster zones before, but this was our first refugee crisis. I just started doing. I organised, planned, and built.

After I had been here for about a month, a donor in the US said he would sponsor me to be here for as long as I needed. So, I called my husband and said, "I want to quit my job and stay in Greece."

Soon after, in June last year, I took over as manager of the Oinofyta camp. I was a little fearful to begin with, but I knew in my heart it was the right thing to do. These guys needed someone to care, to fight, and to advocate for them.

I ended up running the camp for 18 months, until the Greek government shut it down a month ago.

From my perspective, this work is like being a mother. I've raised four children and had several foster children and the job that I do here, even though it involves things like construction and installing electrical equipment, in reality, it's pretty much being a mom.

I'm not a saint. I've learned that love is a choice. For me, some of the more poignant moments have involved people that I don't necessarily really like. When they were informed that the camp was closing, these people came to me and said things like: "You've been like a mother to me, I don't know what I'm going to do without you." And I realised that I had met my goal - which was to take care of them and show them that they were loved. That they're cared about, not forgotten.

When the camp was shutting down, we were told that we'd have time to get our stuff out. We had about a quarter of a million Euros worth of property in the camp. Then, the Greek government, in less than 24 hours, gave me three hours to get it all out.

When that happened, I posted on Facebook: "I'm done. They win, and everybody else loses." That was probably one of my worst nights. How do you fight bureaucracy like that - bureaucracy that makes absolutely no sense?

The next day I woke up to a phone full of messages saying, "What do you need me to do? I will come help." And I thought, "OK, I can do this. We, together, can do this."

...[ Continue to next page ]

Share This Post