The breakthrough moves researchers a small step closer to growing human organs for medical transplant.

This pig embryo was injected with human cells early in its development and grew to be four weeks old. The experiment made headlines when it was announced in early 2017; now, researchers have improved the procedure and tested it on sheep.

Building on a controversial breakthrough made in 2017, scientists announced on Saturday that they have created the second successful human-animal hybrids: sheep embryos that are are 0.01-percent human by cell count.

The embryos, which were not allowed to develop past 28 days of age, move researchers a small step closer to perhaps growing human organs for medical transplant.

Every hour, six people in the United States are added to the national waiting list for organ transplants—and each day, 22 people on the list die waiting. In the U.S. alone, more than a hundred thousand people need heart transplants each year, but only about 2,000 receive one.

In response, researchers are working to artificially expand the organ supply. Some are trying to 3-D print organs in the lab. Others are working on artificial, mechanical organs. And some are making chimeras—hybrids of two different species—in the hopes of growing human organs in pigs or sheep.

Human blood filters through pig lungs as they inhale and exhale in the lab of Lars Burdorf at the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

INCREASINGLY HUMAN

To make chimeras, researchers isolate one animal's stem cells, which can develop into any cell type in the body. They then inject some stem cells from one species into the embryo of another—a tricky procedure to get right.

If the embryo's DNA is hacked so that it does not grow a particular organ, the interloping cells would be the only ones that could fill in the gap. In this way, researchers could grow a human liver inside of a living pig, for example.

In 2017, researchers using this method successfully grew mouse pancreases in rats—and showed that transplants using the pancreas could cure diabetes in diabetic mice. The very next day, Salk Institute researchers announced that they could keep pig embryos injected with human stem cells alive for 28 days.

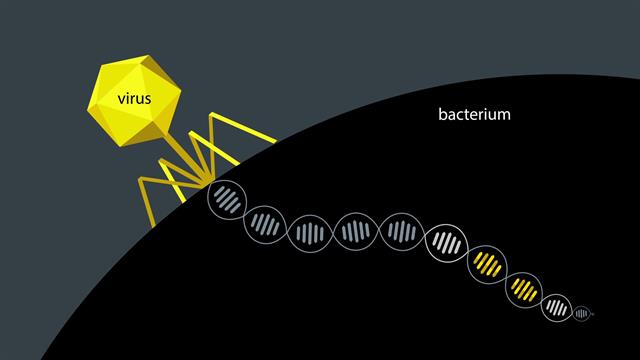

DNA HACKING TOOL ENABLES SHORTCUT TO EVOLUTION

Learn how gene editing technology works in this animated video.

Stem-cell experts lauded the human-pig study, but they noted that the pig embryos' counts of human cells—about one in a hundred thousand—were too low for successful organ transplants.

On Saturday at the 2018 American Association for the Advancement of Science annual meeting in Austin, Texas, researcher Pablo Ross of the University of California, Davis, announced that he and his colleagues have fine-tuned the procedure—boosting human cell counts in sheep embryos to one in ten thousand.

“We think that that's still not probably enough to generate an organ,” Ross said during a press briefing. About one percent of the embryo would have to be human for the organ transplant to work, The Guardian reports. And to prevent immune rejection, extra steps would be needed to ensure that leftover bits of animal viruses are struck from the pig or sheep's DNA. But the work shows progress toward more viable organs.

ETHICAL RAMIFICATIONS

Ross says that the research could be accelerated if it were better funded. The U.S. National Institutes of Health currently forbid public funding of human-animal hybrids, though it signaled in 2016 that it might lift the moratorium. (So far, private donors have funded early research.)

As work continues, ethical scrutiny will also surely intensify. Ross and his colleagues acknowledge the controversial nature of their work, but they also say that they're moving cautiously.

“The contribution of human cells so far is very small. It’s nothing like a pig with a human face or human brain,” Stanford University researcher Hiro Nakauchi, Ross's collaborator, said at the meeting. Nakauchi added that researchers are trying to target where human cells proliferate, to ensure that they don't set up shop in animals' brains or sex organs.

Ross, for one, sees the ever-widening approaches for organ research as cause for optimism.

“All of these approaches are controversial, and none of them are perfect, but they offer hope to people who are dying on a daily basis,” he said. “We need to explore all possible alternatives to provide organs to ailing people.”

Share This Post