China’s growing superpower status and appetite for blockbusters is reshaping the film industry in Australia, where film-makers are being lured by lucrative co-productions

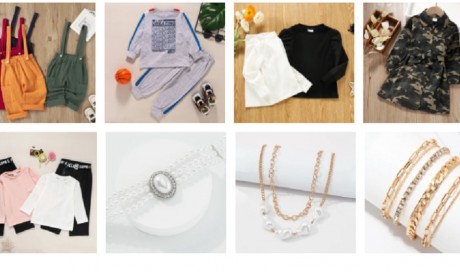

Australian-Chinese co-production Guardians of the Tomb. The film had development and production support from Screen Australia, but was conceived largely for a Chinese audience. Photograph: Arclight Films

When martial arts blockbuster Wolf Warrior 2 earned an astronomical US$854m in China last year – making it the second-highest grossing film in a single market ever – two things happened. First, the economic might of the Chinese film audience was thrown in the spotlight again; soon, commentators enthused, it would eclipse North America as the biggest in the world. Second, commentators couldn’t stopnoticing the film’s nationalistic elements.

One writer combed the film for evidence of China’s geopolitical strategy; the Australian newspaper even called it “Communist propaganda”. (The fact the film climaxes with a morally impeccable ex-People’s Liberation Army soldier stabbing a callous American mercenary in the brain possibly helped this angle along.) Hollywood movies were once regularly accused of “cultural imperialism”, but the rah-rah flag-waving of a Michael Bay film is now so familiar as to be invisible. Yet when China does the same, everybody takes notice.

The response to the film was symptomatic of China’s growing status as global superpower and the cultural influence its cinema is set to wield. The money-making potential of China’s film economy is difficult to resist, but for western film industries, entanglement with China means adjusting their product in ways that go beyond the proscriptions of the local censors.

The Australian film industry has already begun calibrating films to work in China – and the results, so far, have been mixed.

‘We sell the Chinese on the fact that these are Hollywood movies. But secretly they’re Australian’

China’s effect on Hollywood is already evident in small ways: superstar cameos in big franchises like Transformers and X-Men, for instance, or the four minutesadded to the Chinese edit of Iron Man 3. The biggest move, though, is co-productions: projects for which international producers officially partner with China’s state film authorities.

The Great Wall review – Zhang Yimou’s damp squib of a gunpowder plot

So far, these productions have yielded mixed results. In 2017, The Great Wall – a US-China co-production – met with indifference in China and bafflement in the States, where the placement of Matt Damon in the middle of a Chinese medieval fantasy copped accusations of “whitewashing”. As a model of the future of blockbuster cinema it didn’t seem promising. (“The Great Wall targeted American and Chinese audiences but pleased neither”, went one headline.)

The Australian industry has been taking a punt on China too. In 2017, the Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts (Aacta) inaugurated an annual best Asian film award to reflect Australia’s tightening bonds with Asian film industries and the growing impact of the Chinese diaspora on local box office trends (Wolf Warrior 2 was nominated, but lost to India’s Dangal). And November saw the 10-year anniversary of the Australian-Chinese co-production treaty. Eight films have been sanctioned under the treaty, and four have been released.

The latest to reach local screens is Guardians of the Tomb, a cheerfully schlocky creature-feature in which an international cast – including Kelsey Grammer – are menaced by a nest of funnel-web spiders in the booby-trapped tomb of an ancient Chinese king.

Tomb comes from Arclight, an international film sales and financing company that scored a hit in China in 2012 when its Australian-made shark flick Bait 3D earned a surprise US$28m (it made US$800,000 in Australia).

Since then, Arclight has staked out a position at the intersection of Australia, China and Hollywood, starting up a co-production development initiative, Chinalight, with help from Screen Australia. Arclight’s Australian CEO, Gary Hamilton, sees Australia as a gateway to Hollywood for China. “We don’t describe our movies like Guardians of the Tomb as Australian movies, even though they really are,” he says. “We sell the Chinese on the fact that these are Hollywood movies. But secretly they’re Australian.”

But “secretly Australian” films are a compromised proposition for local stakeholders, who must be satisfied with a film made by the local industry but not really for local viewers, and with little in the way of a local story. Guardians of the Tomb, for instance, had development and production support from Screen Australia, but was conceived largely for the Chinese market. Though it opened on 2,500 screens in China, it debuted on only 12 in Australia. So why channel public funds towards a film that lives or dies overseas?

“[Tomb] was entirely shot in Australia,” Hamilton says, “except for three days in China. It’s Australian writers, an Australian director, lots of Australian actors. I think that’s the trade-off. If you’re making Australian films using Australian taxpayer money just for the Australian market, then it becomes a subsidy, because they’ll never make their money back.

...[ Continue to next page ]

Share This Post