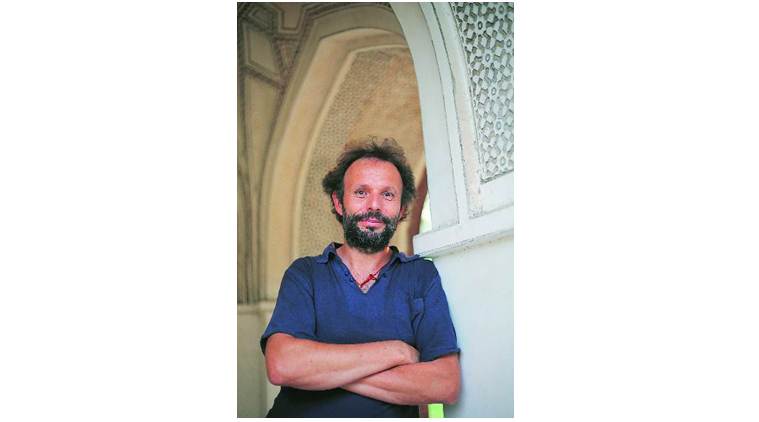

Harald Fuhrmann is being a tourist in Delhi in loose clothes and unruly hair, at the 17th century tomb of Khan-e-Khana in Nizamuddin, when the family preoccupation takes over. Fuhrmann’s young daughter starts performing pieces as part of an audition for child actors while her mother holds the camera. Fuhrmann sits on a bench under a tree and takes out his cellphone that has a picture of him with the Dalai Lama.

“His Holiness is saying that we need to make more drama to tell contemporary stories about the Tibetan people. The Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts (TIPA) needs a director and I said (to a German Tibetan aid organisation), ‘Wherever you need me, I just go’,” he says. Fuhrmann is a theatrical lecturer at the Ernst Busch Academy of Dramatic Arts, Berlin, as well as a prominent director whose idea of theatre is “to do something with reality”. He is also one of the artistes helping to internationalise TIPA’s arts programme.

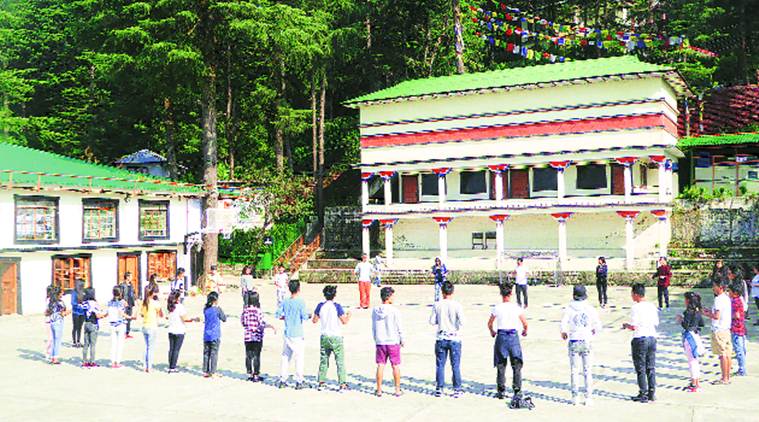

For the past three years, Fuhrmann has been coming to Dharamsala to train students in techniques that involve observing people on the streets and then bringing it on stage. “The actor has to make decisions, such as ‘What story to tell today? Which parts to observe? Which part of reality to bring to the stage and from which angle to look at it?’ This is how we become responsible artistes and not mechanically do what the director wants,” says Fuhrmann.

Eleven years ago, he and 15 people such as actors, puppeteers, dancers, directors and set designers set up the Flying Fish theatre company, let out their apartments and packed their bags to travel through India and Nepal, performing at festivals such as Nandikar as well as on the streets, in villages and towns on the Himalayas. “My dream was to combine work, friendship and travel. What can I do for the world with my profession? Maybe, someone needs theatre,” says Fuhrmann, who has also taught in Iran, Oslo, Australia, New Zealand and Mexico.

He is the first artiste in his family, his father being an engineer and his mother a housewife. “I read a lot of Albert Camus, who talked about how you have to live in the moment and I felt very close to him. Then, I saw him in a film, sitting in a theatre and talking about theatre and I said, ‘Oh, he is doing theatre and I like him so much that maybe I should do theatre’,” says Fuhrmann.

He watched his first play in a tent in an alternative-living part of Berlin. The travelling group was performing a story about the environment and how to live by values rather than money. Fuhrmann has worked as an actor but directing is his signature. Waiting for Godot — which fit in his philosophy that “Life is short. Don’t wait for Godot, just do your thing” — and Goethe’s Faust, Part I, about a scholar who makes a wager with Mephistopheles, are among his repertoire.

Last year, he wrote a play about beliefs after talking to people of different religions, titled Unruhe Im Paradies. His next is Faust II, considered so complex as to be nearly impossible. “Faust is building a dam because he feels that nature should not be stronger than human beings. Thousands of people work for years and, just at the end, Faust becomes old and blind. He thinks he is hearing people digging as they build the dam — at this moment he feels satisfied and dies — but in reality they are digging his grave,” says Fuhrmann.

Several productions have been set in concentration camps and it was during one of these that Fuhrmann found out that his “grandmother was Jewish but she never talked about it”. “Suddenly, I was no longer talking from the point of view of the perpetrator but also the victim,” he says, “When we are in school, German children are told about what was done to the Jews and the world. I retain a strong feeling that somethings like this should never happen again. In the Tibetan issue, the politics of the whole world comes together, about how we behave, what stories we are telling, on business and human rights.”

Share This Post